Introduction

As global populations expand and age, healthcare systems face escalating demands for Acute Care services. These services are crucial for responding to life-threatening emergencies, sudden flare-ups of chronic conditions, and a wide array of health issues requiring swift medical attention. To effectively strengthen healthcare infrastructure, emergency interventions and services must be seamlessly integrated with primary care and public health initiatives. This article will delve into the concept of acute care within this broader context. We will begin by establishing a working definition of “acute care” based on World Health Organization (WHO) standards. Subsequently, we will examine how the absence of a clear definition leads to fragmented service delivery and emphasize the significant contribution of acute care to building integrated healthcare systems aimed at reducing overall morbidity and mortality. Finally, we will propose essential steps that leaders, researchers, and healthcare professionals should consider to advance the development and implementation of robust acute care systems.

Defining Acute Care: A Time-Sensitive Approach

To facilitate meaningful discussions and guide the development of effective healthcare systems, clear and universally understood definitions of health systems and services are paramount. Health systems encompass all organizations, institutions, and resources primarily dedicated to promoting, restoring, and maintaining health.1 Health services, within these systems, are specifically designed to enhance health, diagnose illnesses, provide treatment, and facilitate rehabilitation. They can be viewed as the organized actions required to deliver effective interventions, encompassing promotion, prevention, treatment, rehabilitation, and palliative care, targeting both individuals and populations.1,2

Similarly, a precise definition of acute care is essential. Standard medical definitions often emphasize the critical element of time sensitivity.3 Therefore, acute care services encompass all actions – be they promotive, preventive, curative, rehabilitative, or palliative – directed at individuals or populations, with the primary goal of improving health. The effectiveness of these actions is intrinsically linked to timely and frequently rapid intervention.

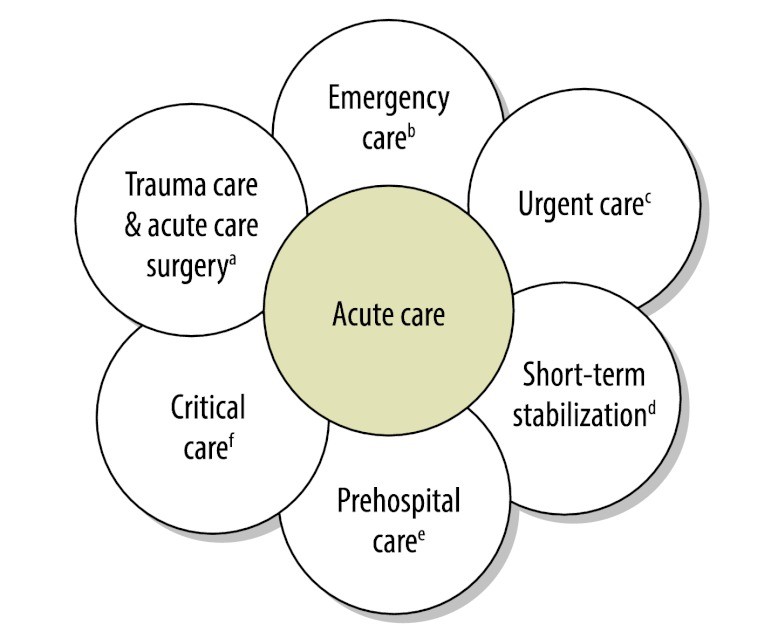

While numerous individually-oriented services benefit from timely delivery, acute curative services stand out as the most time-critical, irrespective of the specific disease. However, in many developing healthcare systems, acute care remains poorly defined and under-resourced. A practical working definition of acute care would encompass the most time-sensitive, individually-focused diagnostic and curative interventions aimed at improving health. We propose defining acute care as the components of the healthcare system, or care delivery platforms, designed to manage sudden, often unexpected, urgent, or emergent episodes of injury and illness that pose a risk of death or disability without prompt intervention. The scope of “acute care” encompasses a diverse range of clinical healthcare functions, including emergency medicine, trauma care, pre-hospital emergency services, acute care surgery, critical care, urgent care, and short-term inpatient stabilization (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Domains in acute care

a Treatment of individuals with acute surgical needs, such as life-threatening injuries, acute appendicitis or strangulated hernias.

b Treatment of individuals with acute life- or limb-threatening medical and potentially surgical needs, such as acute myocardial infarctions or acute cerebrovascular accidents, or evaluation of patients with abdominal pain.

c Ambulatory care in a facility delivering medical care outside a hospital emergency department, usually on an unscheduled, walk-in basis. Examples include evaluation of an injured ankle or fever in a child.

d Treatment of individuals with acute needs before delivery of definitive treatment. Examples include administering intravenous fluids to a critically injured patient before transfer to an operating room.

e Care provided in the community until the patient arrives at a formal health-care facility capable of giving definitive care. Examples include delivery of care by ambulance personnel or evaluation of acute health problems by local health-care providers.

f The specialized care of patients whose conditions are life-threatening and who require comprehensive care and constant monitoring, usually in intensive care units. Examples are patients with severe respiratory problems requiring endotracheal intubation and patients with seizures caused by cerebral malaria.

Domains of acute care including emergency medicine, trauma care, and critical care

Domains of acute care including emergency medicine, trauma care, and critical care

The Consequences of Fragmented Healthcare Systems

In 2007, the WHO underscored the urgent need to strengthen global health systems.4 However, clear definitions and objectives, particularly concerning the delivery of health services, often remain undefined. Countries typically develop lists of priority health problems, often with input from international organizations. Health services are then structured to prevent and manage these prioritized conditions. A critical element frequently overlooked in these processes is the profound impact of time on the effectiveness of health interventions. Preventive strategies primarily aim to reduce the incidence of new cases through interventions that mitigate disease risk. Earlier implementation of preventive measures leads to a more rapid decline in incidence rates. Conversely, curative strategies focus on reducing disability and mortality among existing cases. The priority assigned to curative interventions is determined by their time-sensitivity, effectiveness, and cost. However, the relationship between time and effectiveness varies significantly among curative services. This variability highlights the importance of ensuring patients receive the right intervention in the right place at the right time. Neglecting the time-sensitive nature of curative services leads to fragmentation, characterized by poor care coordination and the inconsistent application of clinical interventions. For instance, delays in administering antibiotics to treat sepsis can result in severe disability or death. Ultimately, fragmented care reduces the number of Disability-Adjusted Life Years (DALYs) that can be averted with available resources, hindering the overall efficiency of healthcare investments.

Acute Care’s Contribution to Integrated Health Systems

Acute care, as a clinical service, directly addresses immediate threats to life or limb, irrespective of the underlying cause. This inherent characteristic positions acute care as a fundamental pillar in building robust, integrated health systems (a horizontal approach). This contrasts sharply with fragmented, condition-specific efforts (vertical programs) that may improve outcomes for particular diseases but fail to enhance the overall functionality of the healthcare system. Importantly, the essential resources – including materials, consumables, and human personnel – needed to establish acute care platforms are often the same resources required for traditional “disease-centered” programs.

It is crucial to dispel common misconceptions surrounding acute care. It is not merely ambulance transport, nor is it solely dependent on advanced technology. Instead, excellent acute care is defined by its temporal urgency – responding swiftly to immediate threats to life and limb – and involves strategically allocating resources to minimize preventable death and disability. Integrating acute care with preventive and primary care creates a comprehensive healthcare paradigm that encompasses all essential aspects of healthcare delivery, ensuring a holistic approach to patient well-being.

The prevailing framework for understanding health challenges categorizes them into communicable diseases, noncommunicable diseases, and injuries. The ongoing global discourse on noncommunicable diseases exemplifies how neglecting the time-sensitivity of curative interventions can lead to fragmented care. In 2008, noncommunicable diseases accounted for 36 million (63%) of the 57 million deaths worldwide.5 A substantial and growing proportion of deaths from noncommunicable diseases and injuries occur in low- and middle-income countries undergoing epidemiological transitions.6 Strategies to combat morbidity and mortality from noncommunicable diseases have predominantly focused on prevention and primary care. For example, the Prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases: guidelines for primary health care in low-resource settings provides guidance for managing diabetes.7 However, only a few points within these guidelines address time-sensitive interventions, despite the fact that conditions like diabetic ketoacidosis can be acutely life-threatening. The critical contribution of acute care to mitigating the increasing burden of disease and injuries has been significantly underestimated in global health strategies.

Acute care plays an indispensable role in preventing death and disability in emergency situations. Primary care, while vital for ongoing health management, is not designed, nor often equipped, to fulfill this crucial function in time-critical scenarios. Within healthcare systems, acute care serves as the initial point of contact for individuals experiencing emergent and urgent medical conditions. A well-defined understanding of acute care will enable the development of metrics to evaluate the effectiveness of acute care services, assess the disease burden addressed by these services, and establish clear objectives for advancing acute care in low- and middle-income countries.8 The currently fragmented specialty areas encompassed by acute care have struggled to achieve significant progress in their respective clinical domains at the international level. This is partly due to a lack of standardized metrics and coordinated healthcare service delivery. Recognizing acute care as an integrated care platform allows these disparate areas to unite and advance a shared agenda with a unified voice, promoting more effective and impactful development.

Key Steps Forward for Acute Care Development

Many simple, effective, and affordable acute care interventions are life-saving, often within the critical first 24 hours. These include interventions provided in basic surgery wards in district hospitals, offering essential treatment for trauma, high-risk pregnancies, and other common surgical emergencies.9,10 Discussions surrounding acute care are gaining momentum, driven by forward-thinking initiatives such as the establishment of the African Federation for Emergency Medicine in 2009 and the Academic Emergency Medicine Consensus Conference dedicated to “Global health and emergency care: a research agenda” in May 2013. However, several key steps are still needed to further advance the development of acute care systems globally:

- Developing an acute care service delivery model specifically tailored for low- and middle-income countries. This model should operate in conjunction with existing preventive and primary care services, addressing both life-threatening and limb-threatening conditions, as well as acute exacerbations of prevalent noncommunicable diseases.

- Improving coordination among acute care service providers, including emergency physicians, surgeons, and obstetricians. Enhanced collaboration will ensure the efficient and effective delivery of critical acute care services, optimizing patient outcomes.

- Developing robust research methodologies to accurately quantify the burden of acute care diseases and injuries. This research should include health economics and cost-effectiveness analyses to provide compelling evidence for integrating acute care as a core component of national health systems.

- Facilitating national and international dialogues to promote a deeper understanding and encourage the enhanced integration of acute care within local and national healthcare systems. Open communication and knowledge sharing are crucial for driving progress and fostering collaborative solutions.

This article serves as a call to action for leaders, policymakers, and academics to recognize the vital contribution of acute care systems in managing patients with communicable and non-communicable diseases, as well as injuries. However, the development of such acute care systems must not be misused as justification for diverting resources to poorly equipped and mismanaged health facilities. Aligning key stakeholders, both within and across countries, to support the development of the optimal balance of acute and preventive services is an urgent priority for strengthening health systems and improving societal well-being in the face of a growing global disease burden.

Acknowledgements

The authors extend their sincere gratitude to Linda J Kesselring for her invaluable assistance in the preparation of this manuscript.

Funding:

JM Hirshon received funding from the National Institutes of Health Fogarty International Center (Grant 5D43TW007296).

Competing interests:

None declared.

References

1 World Health Organization. Everybody’s business: strengthening health systems to improve health outcomes: WHO’s framework for action. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2007.

2 van Olmen J, Marchal B, Van Damme W, Kegels G, Hill PS. Frameworks for understanding and analysing health systems strengthening. Health Policy Plan 2009;24:414–32. PubMed

3 Moskop JC. The conceptual basis of the definition of futility. Am J Bioeth 2005;5:42–4. PubMed

4 Chan M. WHO director-general addresses sixty-first World Health Assembly. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008.

5 World Health Organization. 2008–2013 action plan for the global strategy for the prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2008.

6 World Health Organization. Global health risks: mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2009.

7 World Health Organization. Prevention and control of noncommunicable diseases: guidelines for primary health care in low-resource settings. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2012.

8 Mock CN, Joshipura M, Goosen J, Kobusingye O, Nguyen T, Arreola-Risa C, et al. Strengthening care for the injured in developing countries: essential actions. Bull World Health Organ 2004;82:655–61. PubMed

9 Debas HT, Gosselin R, McCord C, Thind A. Surgery. In: Jamison DT, Breman JG, Measham AR, Alleyne G, Claeson M, Evans DB, et al., editors. Disease control priorities in developing countries. 2nd ed. Washington, DC: World Bank; 2006. pp. 1245–63.

10 Ozgediz D, Jamison D, Schecter W, Farmer P. Surgery and global health: a Lancet Commission. Lancet 2009;373:2248–7. PubMed