Japan is often lauded for its impressive health indicators and long life expectancy. A cornerstone of this success is its universal health care (UHC) system, ensuring that all citizens and long-term residents have access to medical services. But while Japan boasts universal coverage, a closer examination reveals a system grappling with unique challenges, particularly concerning its human and material resources.

Japan achieved universal health insurance coverage in 1961, a remarkable feat that provides a safety net for its entire population. This system is primarily funded through a combination of payroll taxes, individual income taxes, and patient co-payments. It allows individuals to choose their healthcare providers and receive treatment without fear of exorbitant costs bankrupting them. In many ways, Japan’s UHC system is a model for accessible and affordable healthcare.

However, beneath the surface of universal access lie structural issues that impact the robustness and future sustainability of Japan’s medical care system. One of the most distinctive features, as highlighted by studies, is Japan’s reliance on a private capital-dependent healthcare delivery model. Unlike many other developed nations with strong public healthcare sectors, Japan’s system is heavily influenced by private hospitals and clinics. These private institutions operate largely as independent entities, bearing their own financial risks. This structure, where even non-profit hospitals often require personal guarantees from their directors for investments, hinders consolidation and regional coordination, leading to a fragmented landscape.

Historically, governance in regional healthcare provision has been underdeveloped in Japan. For instance, regulation of hospital bed numbers was only introduced relatively recently in 1985. This lack of centralized planning has resulted in a system where resource allocation and capital investment are largely determined by individual medical institutions. The consequence is a facility-centric approach rather than a community-centered one, where regional needs are holistically addressed and resources are strategically distributed. This decentralized approach leads to duplication of services and investments, even within the public sector, and a lack of functional differentiation and coordination among medical institutions. While Japan presents a high number of hospital beds per capita internationally, the system struggles with efficiently allocating resources to higher-level care and integrated long-term care solutions.

Figure 2.

Figure 2.

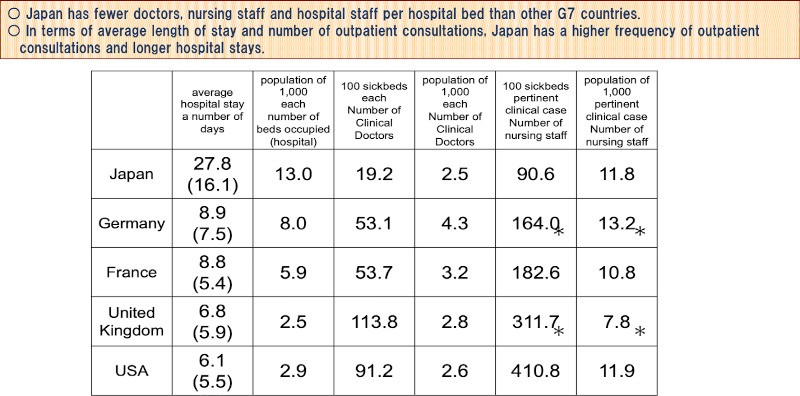

The issue of resource constraints is further emphasized when examining staffing levels. While the overall number of physicians per population in Japan might seem reasonable, the physician-to-hospital-bed ratio paints a different picture. Compared to G7 countries like the U.S., UK, Germany, and France, Japan has a significantly lower number of doctors per hospital bed. In fact, the number is approximately one-fifth of the U.S. and UK, and less than half of Germany and France. This disparity is not improving; as medical care advances and becomes more complex in other nations, the number of doctors per bed increases, but in Japan, this number has stagnated. The same concerning trend is observed with nursing staff levels, as illustrated in Figure 2, which compares hospital staff per bed across G7 countries. This figure, “International comparison of the Number of hospital staff per hospital bed, average length of stay and discharge in G7 countries,” sourced from the Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, underscores Japan’s relatively lower staffing levels in hospitals.

This resource disparity has tangible consequences, notably in the average length of hospital stays. Despite efforts to shorten hospital stays, they remain longer in Japan compared to Western countries. A well-established correlation exists between the length of hospital stay and the number of doctors available; fewer doctors often correlate with longer stays. This suggests a reality of “thin-on-the-ground medical care” in Japanese hospitals, where resources are stretched.

Further compounding these challenges is the prevalence of smaller hospitals. Data indicates that a significant majority, 93%, of private hospitals in Japan have 199 beds or fewer. These smaller hospitals constitute a substantial 70% of all hospitals in the country. While a widespread distribution of medical facilities may seem to offer easy access to care, it raises questions about the efficient allocation of limited medical resources and the capacity for specialized treatments within these smaller institutions.

The workload on Japanese physicians is demonstrably heavier. Simple calculations reveal that a hospital physician in Japan is responsible for approximately 5.5 inpatients, whereas in the U.S., the figure is around 1.1. This means Japanese hospital doctors manage five times as many inpatients as their American counterparts. Similarly, in outpatient settings, Japanese physicians handle significantly higher volumes of patients annually compared to U.S. physicians. This demanding work environment, inherent within the framework of easily accessible universal healthcare, puts immense pressure on medical professionals.

The root of these issues can be traced back to the rapid expansion of medical demand following the achievement of universal health insurance. Instead of proactively developing human and material resources to match this increased demand, the system has largely relied on private medical institutions with limited capacity. The fee-for-service payment system, while intended to ensure the financial viability of these institutions, may inadvertently incentivize the proliferation of medical facilities without necessarily addressing the underlying issues of resource allocation and workload.

Consequently, hospital doctors and staff experience chronic overwork, hindering their ability to provide intensive inpatient care. Hospitals often struggle with undifferentiated diagnostic responsibilities and adapting to evolving disease patterns. Many lack the facilities and staffing necessary for advanced medical functions. The financial self-sufficiency model for medical institutions, while aiming for sustainability, has created a system resistant to significant reform, as reimbursement structures are largely designed to maintain the existing status quo.

The COVID-19 pandemic starkly exposed these inherent vulnerabilities within Japan’s healthcare system. The strain on resources and the fragmented nature of the system became readily apparent, highlighting the urgent need for reforms to ensure both the sustainability and resilience of Japan’s commendable, yet challenged, universal health care system.