Studebaker, an American automotive brand with a rich history dating back to the 19th century, holds a special place in the hearts of car enthusiasts. Known for its innovative designs and independent spirit, the question often arises: why did Studebaker Cars ultimately disappear from the market? Examining the factors that led to Studebaker’s closure reveals a complex interplay of economic pressures, labor issues, and strategic missteps within the fiercely competitive automotive industry.

Labor Costs and Union Challenges

One of the significant burdens on Studebaker’s financial health was its struggle with labor unions and associated costs. As highlighted in automotive history analyses, after World War II, Studebaker, unlike its Detroit Big Three competitors, didn’t withstand major strikes to negotiate more favorable labor agreements. James Nance, the last president of Packard (which merged with Studebaker), pointed out this critical misstep, stating that Studebaker’s inability to take a strike and reach reasonable compromises on wages and benefits put them at a permanent disadvantage. This acceptance of union demands immediately post-war, as noted by chairman Paul Hoffman’s decisions, set a precedent that the company struggled to overcome, leading to higher operational costs compared to its rivals.

The Crippling Break-Even Point

The financial ramifications of these high labor costs became starkly evident when Packard accountants scrutinized Studebaker’s books after the merger in 1954. They discovered a shocking reality: Studebaker’s break-even point was a staggering 50,000 cars higher than their best annual sales volume. This meant Studebaker needed to sell an exceptionally large number of cars just to avoid losing money, a target consistently out of reach. A former Studebaker designer even illustrated this cost disparity by pricing the iconic 1953 Starliner using General Motors’ costing methods. The result was alarming – GM could have offered the same Studebaker Starliner for $300 less, a substantial price difference at the time, showcasing Studebaker’s cost inefficiency.

Marketing Missteps and Production Planning

Beyond financial woes, Studebaker also suffered from marketing and production planning miscalculations that further hampered their success. Despite having strikingly beautiful and desirable models designed under the guidance of Raymond Loewy, such as the 1953 Starliner and Starlight coupe, Studebaker’s sales and marketing teams misjudged market demand. In 1953, they overproduced sedan models while underestimating the immense popularity of the Starliner hardtops and coupes. This production mix was the antithesis of what the public wanted, leading to inventory issues and lost sales opportunities for the more profitable and sought-after models.

The Unfulfilled Conglomerate Dream

In retrospect, some industry observers believe that Studebaker’s fate might have been different had a proposed plan for a conglomerate of independent automakers materialized. George Mason of Nash Motors foresaw the looming challenges for independent car manufacturers as early as the 1940s. He attempted to create a powerful alliance comprising Studebaker, Packard, Nash, and Hudson. Mason believed that consolidating these independent brands would create economies of scale necessary to compete with the automotive giants. However, this vision failed to gain traction, and the missed opportunity to form such a conglomerate arguably sealed the fate for Studebaker and other independent marques in the long run.

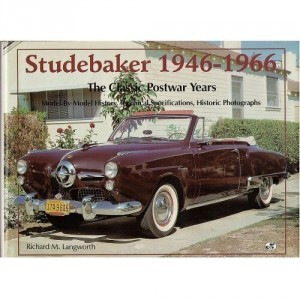

Design Excellence: A Lasting Legacy

Despite its ultimate failure, Studebaker cars are celebrated for their distinctive and often groundbreaking designs. The brand benefited immensely from the collaboration with renowned industrial designer Raymond Loewy and his team, who were instrumental in creating the stunning 1953 Starliner and the futuristic 1963 Avanti. Loewy’s design philosophy and his talented team, including designers like Bob Bourke (Starliner), Bob Andrews, John Epstein, and Tom Kellogg (Avanti), ensured Studebaker cars stood out aesthetically. Even when facing financial constraints in the 1960s, Studebaker president Sherwood Egbert enlisted Brooks Stevens, who skillfully facelifted existing models like the Lark and Hawk and introduced innovative concepts such as the Wagonaire with its sliding rear roof.

While these styling efforts, both from Loewy and Stevens, were commendable, they were ultimately “reskins” of older platforms. Despite exciting new design proposals for 1966 and beyond, time had run out. Studebaker closed its main South Bend, Indiana factory in December 1963, and the final curtain fell when the Hamilton, Ontario plant ceased production after completing the 1965-66 models.

In conclusion, the reasons for Studebaker’s demise are multifaceted, ranging from unsustainable labor costs and a high break-even point to marketing miscalculations and missed strategic alliances. While management decisions and economic pressures played a crucial role, Studebaker’s legacy of innovative design and independent spirit continues to resonate within the automotive world, reminding us of a brand that dared to be different.